It was a starlit winter evening in southern India as we barreled down a rural road through a Tibetan settlement village in our tuk-tuk, a three-wheeled motorized taxi. The sputter of the motor was interrupted only by the joyful laughter of our Tibetan Buddhist monastic friends as they raced us in their own tuk-tuk on our way to watch the Gorshey, a traditional Tibetan circle dance. We were in India that winter of 2022 for the inaugural Research Training workshop for the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative. The goal of the workshop was to begin to lay the foundation for cross-cultural research collaborations between academic scientists and Tibetan Buddhist monastics on topics such as the mind, health, well-being, and human flourishing. The beauty of that moment in our tuk-tuk was balanced by a soft sadness, knowing that we would be heading home to Chicago the next morning. Yet we also knew we would return to India—soon and often—and that we were witnessing just the beginning of what the Dalai Lama calls the 100 Year Project.

The Vision for the 100 Year Project

The Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959 following the Chinese occupation of Tibet, establishing a government in exile in Dharamsala, where he still resides today. Many Tibetans, both lay people and monastics, have since joined him in India and rebuilt their communities there, living as refugees. Major Tibetan monastic universities have been re-established in India, where tens of thousands of Tibetan monks and nuns are currently pursuing their studies. A monk himself, the Dalai Lama is well familiar with the value and potential of monastic education, and thinks deeply about how these scholars can best apply their training for the greater good.

As beautifully described in his book The Universe in a Single Atom1, His Holiness envisions a long-term collaboration between academic scientists and Tibetan Buddhist monastics to explore both ancient and contemporary questions in the service of humanity. He refers to it as the 100 Year Project in recognition of the time it may take to fully realize this ambitious vision. With a lifelong interest in science, the Dalai Lama has been, for decades, engaging in dialogues that explore the intersections and distinctions between academic science and the enduring wisdom traditions of India and Tibet. The Mind & Life Institute has played a central role in facilitating these dialogues for nearly 40 years and promises to be the guiding force for the future of this cross-cultural exchange.

Both science and Buddhism share an inquiry mindset marked by a deep curiosity and commitment to investigate the fabric of reality as it is, rather than what we hope it might be.2 Indeed, His Holiness has referred to the Buddha as an “ancient Indian scientist.” Science and Buddhism also share a willingness to let go of long-held beliefs when new evidence diverges from existing models or theories.3 For example, while Buddhism values scripture and ritual, the Dalai Lama asserts4 that scriptural authority should not outweigh knowledge gained through experience and reason.

Despite this shared mindset, science and Buddhism frequently differ in their methods. Scientific inquiry generally adopts a third-person viewpoint,5 emphasizing measurement, quantification, and experimental methods. In contrast, Buddhist traditions place greater value on first-person experience,6 focusing on direct observation of internal and external phenomena, supported by reasoning and analytical investigation.

…science and Buddhism share an inquiry mindset marked by a deep curiosity and commitment to investigate the fabric of reality as it is…

Many scientists7 and Buddhist thinkers, including the Dalai Lama, believe the time is ripe for deeper collaborations between these two traditions, with the goal of addressing some of humanity’s most pressing challenges. To set the foundation for these collaborations,8 the Dalai Lama has been working with organizations like the Mind & Life Institute and Mind & Life Europe on initiatives to facilitate conversations between science and spirituality. This includes nearly 40 dialogues organized by Mind & Life between the Dalai Lama and leading scientists, philosophers, and contemplatives exploring topics such as consciousness, emotion, human suffering and flourishing, and the health of the planet.

As these collaborations progressed, it became evident9 that the Tibetan monastic community would benefit from more specific training in academic science to fully participate in such dialogues. Tibetan monks and nuns are trained deeply in logic and philosophy as they study the Buddhist teachings; however, their education has not historically included topics and approaches from academic science. The Emory-Tibet Science Initiative emerged10 from the hope of bringing this additional knowledge into monastic training.11

The Emory-Tibet Science Initiative

His Holiness has a longstanding relationship with Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, where he was named a Presidential Distinguished Professor in 2007. This relationship began, in part, when the Dalai Lama encouraged a Tibetan Buddhist monk named Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi to explore academic philosophy and the science of mind. Following this advice, Geshe Lobsang entered graduate school at Emory, earning his PhD in the 1990s. Geshe Lobsang is now a Professor of Religion at Emory where he directs the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics. However, the formal collaboration between the Dalai Lama and Emory University began in 1998, when the Dalai Lama was invited to inaugurate the Emory-Tibet Partnership, an academic affiliation between Emory and Drepung Loseling Monastic University in India. In 2008, the Dalai Lama and Geshe Lobsang formally launched the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI) in collaboration with the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in India.

ETSI’s goal is to integrate academic science into the education of thousands of displaced Tibetan Buddhist and Himalayan monastics living in India, reflecting the first major change in the monastic curriculum in six centuries. Supported by ETSI, Tibetan monasteries have hosted science educators from dozens of universities around the world for an annual science education program for monks and nuns. Over the course of a six-year long implementation phase, monastics study with experts in various disciplines, including physics, neuroscience, biology, and philosophy of science. ETSI aims to bridge two complementary systems of knowledge by educating future scientific collaborators in the study of mind and body.

Critically, ETSI’s work extends beyond science education, striving toward a true cross-cultural collaboration and conversation that is in line with the vision of the 100 Year Project. Accordingly, academic scientists are as much the students in this collaboration as they are the teachers. This program allows them to learn about Buddhist philosophy and science of mind, and what it can offer to our understanding of consciousness and integrative approaches to health and well-being.

Academic scientists are as much the students in this collaboration as they are the teachers.

In 2019, ETSI graduated its first cohort of monastic students from the implementation phase. This included 233 monastics from nine monastic institutions across India who completed the six-year science curriculum. To further advance His Holiness’s vision, the next phase of ETSI, the sustainability phase, is designed to provide Tibetan monastics with opportunities to train in science pedagogy and research methodology and fully engage in scientific research. The research component of this phase of ETSI is co-directed by Robin (co-author here) and Nicole Gerardo, a professor of Evolutionary Biology at Emory University.

As a storysharer turned filmmaker, Park Krausen (co-author here) recognized the historic significance of the newest chapter of this dialogue sparked by His Holiness. As it was unfolding largely within the walls of academic and monastic institutions, Park, who was already involved with ETSI, felt compelled to help amplify this conversation and its potential benefit for humanity. With ETSI’s blessing, she was fortunate to film many of the early interactions of this phase, documenting the transformative power of these collaborations. The camera became an extension of her curiosity as she asked: What happens when these worlds come together, and what new insights can emerge? What she captured sparked the forthcoming documentary currently titled: Frontiers of the Mind: The 100 Year Project.

Learn more about the Dalai Lama’s vision for the 100 Year Project in this short preview of Frontiers of the Mind.

Training Monastics in Research

The research training program of ETSI creates exciting opportunities for Tibetan monastics and academic scientists to engage in meaningful collaboration. First, it aligns with the body of literature that emphasizes the value of doing science12 to learn science. Second, it offers both the monastics and scientific faculty opportunities to more deeply explore similarities and differences in the investigative methods between science and Buddhism. And third, it allows monastics to move from acquiring scientific knowledge in a classroom setting to generating and using scientific knowledge to ask questions and address topics that are relevant to their traditions and culture.

On this latter point, most contemplative science research to date has been conducted by academic scientists at Western institutions. While this work is incredibly valuable, there is a growing opportunity for the monastic community to actively engage as true collaborators in exploring these questions. Centering this research within the monastic community will likely generate new questions and perspectives on contemplative science that are rooted more deeply in Indo-Tibetan wisdom traditions. Moreover, this work could also help address pressing health and environmental challenges faced by the Tibetan refugee population, such as water quality and rising rates of diabetes.

ETSI just completed its fourth year of research training and we are inspired by its evolution. The structure of the research training program involves an annual, multi-week winter workshop at the Drepung Loseling Meditation and Science Center in India, along with ongoing experiential research opportunities for monastics. The first two years of the program focus primarily on developing conceptual and technical skills, including overviews of research methods, experimental design, statistics, the structure of scientific articles, and scientific presentation skills.

Given the monastics’ interest and extensive training in meditation and psychology, we have centered their research training on neuroscience and methods for measuring human physiology in the brain and body. This included building a neuroscience lab at the Drepung Loseling Meditation and Science Center to record brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG), as well as creating a sleep lab to enable data collection from participants throughout the night. The development of the sleep lab was led by Professor and Mind & Life Fellow Ken Paller from Northwestern University, an expert on the neuroscience of sleep and memory. This on-site laboratory provides monastics with hands-on experience conducting neuroscience experiments, including collecting, processing, and analyzing scalp-recorded brain activity. Park served as the initial subject for the monastic scientists’ first study in the sleep lab.

The focus of years three and four of the research training program is to provide experiential learning opportunities in science by supporting monastics in developing and conducting their own research studies. Approximately 60 monastics were organized into eight groups based on shared scientific interests. Each group spent about a week formulating hypotheses, developing experimental methods, selecting measures, and identifying potential participants. With support from over 20 ETSI-affiliated academic scientists and faculty from around the world, along with eight local Tibetan science teachers, the monastics then spent the following year carrying out their projects. This process included weekly meetings with their research teams, monthly virtual meetings with ETSI faculty mentors, and quarterly check-ins with program directors Robin and Nicole.

Bringing New Perspectives to Research

The research questions and methods chosen by the monastics were deeply inspiring, reflecting their unique cultural perspective and rigorous training in Buddhist philosophy and contemplative practice. For example, one study used EEG to compare brain activity in monastics meditating on Prasangika versus Cittamatra teachings of Madhyamika. Madhyamika is a school of Buddhism, and its teachings on emptiness and the “middle way” are foundational to the Tibetan monastic curriculum. The Prasangika versus Cittamatra approaches present different philosophical and contemplative methods for engaging with the teachings on emptiness. This study is the first to systematically examine shared versus distinct effects of these two philosophical traditions on the brain.

Another project involved a collaboration with Ken Paller and his team, including Mind & Life Varela award grantee Gabriela Torres Platas, post-doctoral researcher James Glazer, and graduate student Daniel Morris. This project explores the integration of a Tantric Buddhist practice known as dream yoga with research on the neuroscience of lucid dreaming. A lucid dream occurs when the dreamer becomes aware they are dreaming and can sometimes influence the dream’s content. In pioneering research, Dr. Paller and his team developed a method13 for real-time communication with individuals in a lucid dream state by instructing them to move their eyes in specific patterns to signal ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. They confirm lucid dreaming using a distinct profile of brain and muscle activity. Dream yoga is an ancient Buddhist practice in which a practitioner becomes lucid during a dream and engages in specific forms of meditation, visualization, and analytic inquiry. It is believed that these practices are especially powerful in the dream state due to greater access to more subtle or foundational aspects of consciousness. Using the sleep lab at Drepung Loseling, the monastic research team aims to measure brain activity in both novice and advanced dream yoga practitioners as they meditate during lucid dreaming.

Other monastic-led research projects focus on pressing health and environmental issues facing the Tibetan communities living in exile. For example, one team collaborated with a local Tibetan physician to address rising rates of diabetes in the settlement camps. They conducted blood draws to measure several indicators of cardiometabolic health—such as triglycerides and lipid levels—before and after an eight-week intermittent fasting intervention. Another team investigated water quality by analyzing drinking water samples from their monasteries.

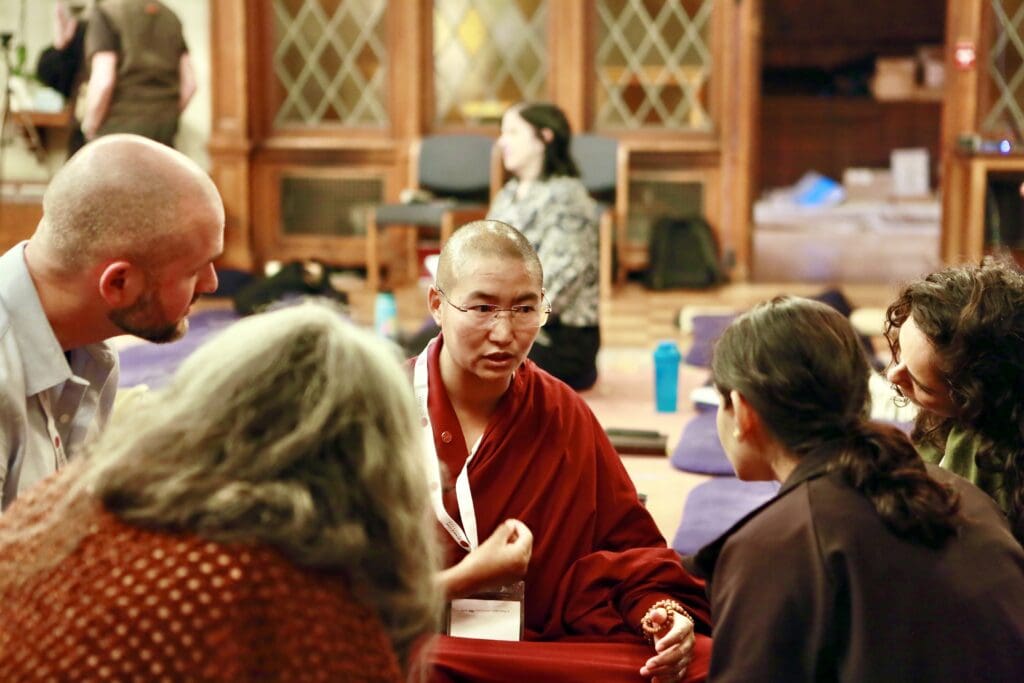

Photo courtesy of Frontiers of the Mind.

The monastics worked diligently for over a year on their research projects, which culminated in the first-ever monastic-led research conference in May 2024. Supported by ETSI, the conference was held at the Dalai Lama Library and Archives in Dharamsala, India. One of the more extraordinary moments was the scientific poster session held in the courtyard of His Holiness’s main temple. Here, the monastic teams presented their research findings not only to conference attendees, but also to members of the public from a variety of geographical and spiritual backgrounds who were visiting the temple that day. The public actively engaged with the monastic scientists, and there was a confluence of spirited scientific and spiritual debate, coupled with the sounds of Buddhist chanting and the sights and scents of the Himalayan highlands on a crisp spring afternoon. During the poster session, Robin spotted his colleague Nicole Gerardo across the courtyard. The two exchanged smiles, recognizing they were witnessing an important moment in the dialogue between Buddhism and science. Park and her colleague, Tibetan filmmaker Kalsang Damdul, were there to capture the experience through the lens of a storysharer.

In this podcast episode, Robin shares more about the training of Tibetan monastics in science and the study of lucid dreaming with monks.

Northwestern University Neuroscience Internship Program

A final aspect of the ETSI research training program is a two-month internship at Northwestern University focused on human neuroscience for Tibetan lay science teachers and monastic scholars. This internship emerged from the recognition that a deeply immersive and intensive training experience is important for helping monastics develop both the theoretical and technical skills to conduct research. Along with Robin, the internship faculty are Northwestern professors Ken Paller and Marcia Grabowecky, and Park serves as the Program Director. Its success is made possible by the incredible efforts of staff, postdoctoral trainees, and students involved. The internship provides hands-on training in human neuroscience methods, including functional and structural brain imaging and electrophysiology, along with conceptual coursework in the neuroscience of emotion, sleep, memory, and attention.

We recently completed the third year of this program, with each year’s cohort of four monastics selected by ETSI and one Tibetan science teacher traveling from India to Northwestern. We are continually inspired by the dedication and sincerity each participant brings to the training, with the intention of fulfilling His Holiness’s vision. Our collective vision is for monastics who complete the internship at Northwestern to return to India equipped to serve as leaders and facilitators of research training for incoming cohorts.

Looking Toward the Future

The soft sadness that we felt in that tuk-tuk several years ago, knowing we would have to say goodbye to our dear monastic friends and colleagues the next day, has since evolved into a deep gratitude for the opportunity to work so closely with them over the years in advancing the collaboration between Buddhism and science. It is the privilege of our lifetime to contribute to the Dalai Lama’s vision for the 100 Year Project.

This gratitude is further buoyed by a sense of excitement and optimism for all that lies ahead. Monastic scientists are increasingly taking central roles in developing and implementing research projects, not only within ETSI but also in collaboration with Mind & Life scientists. For example, Marieke van Vugt at the University of Groningen is working with monastic researchers to examine the effects of debate training and analytic meditation on psychological well-being and brain activity.

Furthermore, Richard Davidson is leading an international collaboration that includes monastic scientists to investigate tukdam14, a meditative state believed to occur at the time of death.

There are also critical developments underway to support the scientific education and research training of Buddhist nuns, who have been historically underrepresented in the monastic tradition. Mind & Life has taken a leadership role by establishing scholarships that enable nuns to attend and present at its annual Summer Research Institute (SRI). In addition, historic efforts are now underway to build science education centers and research laboratories at Buddhist nunneries in India. Several nuns have already completed both the implementation and sustainability phases of the ETSI research training program, including the neuroscience internship at Northwestern. Continued support and investment in these training opportunities will be vital for fostering scientific engagement within the broader Buddhist community.

Finally, monastic scientists are increasingly playing a central role in the dialogue between Buddhism and science. For example, three monastic scientists in the ETSI research community—Geshe Sangpo, Geshe Thabkhe, and Venerable Ani Choyang—will serve as faculty at the upcoming Mind & Life dialogue on “Minds, Artificial Intelligence, and Ethics” in Dharamsala, India. The future is indeed bright for a deepening and ever-evolving conversation between Buddhism and academic science, and we are hopeful that monastic scientists will become a central part of this dialogue.

In closing, we want to re-emphasize that it is important for academic scientists and artists to be at least as much, if not more, the students in this cross-cultural collaboration and co-education. The scientific study of mind is relatively new, and in some ways rather shallow. In contrast, the Indo-Tibetan perspective is grounded in 2,500 years of investigating the mind, offering exquisite road maps for understanding the nature of human suffering, and the potential for human flourishing, wisdom, and compassion. By learning from and directly collaborating with monastics, contemplative science can uncover new and unexpected questions to investigate, and pursue horizons it would not have otherwise envisioned.

Furthermore, science needs an ethical framework to guide it through a future characterized by unprecedented opportunity (e.g, artificial intelligence, synthetic biology), but also considerable challenges and risks. The spirit of awakening and compassion that permeates Tibetan Buddhism is an ideal north star to guide this ethical framework.

Our sincere hope and intention are that the collaboration between academic science and Buddhism not only engages with traditional questions of mind and matter, but also remains deeply committed to supporting the preservation and flourishing of Tibetan people and culture. His Holiness the Dalai Lama provides a roadmap for this rich collaboration in his teachings and writings on the 100 Year Project. We’re honored to support it in any way that we can.

Have something to share? Email us at insights@mindandlife.org.

Support our work with a gift to Mind & Life.

Notes

- 1.

Dalai Lama, H. H. (2005). The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality. New York: Morgan Road Books.

- 2.

Ladyman, J. (2002). Understanding Philosophy of Science: Introduction. New York: Routledge.

- 3.

Dalai Lama, H. H. (2005).

- 4.

Jinpa, T. (2010). Buddhism and Science: How Far Can the Dialogue Proceed? Zygon 45, 871–882.

- 5.

Popper, K. R. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: Hutchinson of London.

- 6.

Wallace, B. A. (2003). Buddhism and Science: Breaking New Ground. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- 7.

Davidson, R. J., and Lutz, A. (2008). Buddha’s Brain: Neuroplasticity and Meditation [in the Spotlight]. IEEE Signal. Process. Mag. 25, 176–174.

- 8.

Eisen, A., Zivot, J., Nusslock, R., Balgopal, M. M., Hue, G., & Negi, L. T. (2022). The Emory-Tibet Science Initiative, a Novel Journey in Cross-Cultural Science Education. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 89.

- 9.

Sonam, T. (2019). “Incubating Western Science Education in Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries in India,” in Science Education in India (Singapore: Springer), 27–45.

- 10.

Nusslock R., Gerardo N.M., Mascaro J.S., Shreckengost J., and Balgopal M.M. (2022) Integrating Authentic Research Into the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 767547.

- 11.

Eisen et al. (2022).

- 12.

National Research Council (2012). Discipline-based Education Research: Understanding and Improving Learning in Undergraduate Science and Engineering. Editors S. R. Singer, N. R. Nielsen, and H. A. Schweingruber (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press).

- 13.

Konkoly, K.R., Appel, K., Chabani, E., Mangiaruga, A., Gott, J., Mallett, R., Caughran, B., Witkowski, S., Whitmore, N.E., Mazurek, C.Y., Berent, J.B., Weber, F.D., Turker, B., Leu-Semenescu, S., Maranci, J.B., Pipa, G., Arnulf, I., Oudiette, D., Dresler, M., & Paller, K.A. (2021). Real-time dialogue between experimenters and dreamers during REM sleep. Current Biology, 31, 1417 – 1427.

- 14.

Lott, D. T., Yeshi, T., Norchung, N., Dolma, S., Tsering, N., Jinpa, N., Woser, T., Dorjee, K., Desel, T., Fitch, D., Finley, A. J., Goldman, R., Ortiz Bernal, A. M., Ragazzi, R., Aroor, K., Koger, J., Francis, A., Perlman, D. M., Wielgosz, J., Bachhuber, D. R. W., Tamdin, T., Sadutshang, T. D., Dunne, J. D., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2021). No detectable electroencephalographic activity after clinical declaration of death among Tibetan Buddhist meditators in apparent Tukdam, a putative post‑mortem meditation state. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 599190.

The Mind & Life Institute

The Mind & Life Institute