One of the central elements of caring involves the capacity to see things from another person’s point of view. In psychology, this ability is referred to as “theory of mind.” If we want to be able to respond to someone compassionately, we must first understand what he or she may be thinking, feeling, or perceiving—we must have a theory of his or her mind.

In order to do that, we must shift from our own perspective and “put ourselves in their shoes.” In that process, however, we don’t completely abandon our own view. Since we can’t observe others’ minds directly, we instead make use of personal memories and experiences, intuiting what another person is going through by way of analogy. If you think about it, this is actually a complicated set of cognitive operations, but we make this shift effortlessly, many times each day.

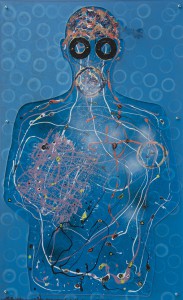

Not surprisingly, the brain mechanisms for processing self-related experiences are also used for interpreting the mental states of others. Neuroscientific research has implicated a region called the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) as important for theory of mind. The TPJ is also involved in processing self-related information (e.g., the spatial unity of self and body, or “embodiment”), and is key for distinguishing between self and other. Several medial frontal and parietal areas appear to work with the TPJ to form a brain network that underlies theory of mind.

So, if we want to become more caring, the first question we might ask is whether it’s possible to enhance our theory of mind. In psychology, theory of mind has not historically been viewed as a skill that might vary among the population, or be trainable. Until recently, theory of mind has been viewed as a capacity that is either “normal” or grossly impaired, as has been suggested in autism. However, psychology research is now beginning to examine differences in theory of mind ability in healthy adult populations. For example, it was recently shown that people who read literary fiction have improved scores on theory of mind tests.

Researchers have not yet examined whether meditation affects theory of mind ability directly, but some contemplative practices appear to target exactly this capacity.

Richard Davidson and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin studied expert and novice meditators, scanning their brains while they performed a compassion-based meditation. During the scans, participants were also exposed to emotional sounds. The study showed that both during meditation and in response to the sounds, expert meditators had greater brain activation than novices in several areas including the TPJ. In fact, more than any other area, activity in the TPJ was most strongly related to meditative expertise. This suggests that experienced meditators might be more primed to share emotion with, or take the perspective of, another person.

Another study, at Emory University, tested people’s ability to infer others’ emotions by looking only at their eyes, a standard test of “empathic accuracy” that is closely related to theory of mind. Compared to a control group trained in healthy living, participants trained in compassion were more likely to improve their accuracy on the test, indicating they were better able to judge the emotions of other people based on subtle cues. In addition, the improvement in scores correlated with increased brain activity in frontal cortical regions known to be involved in empathic accuracy and theory of mind.

Finally, a recent longitudinal study of brain structure at Harvard found that the TPJ and other regions implicated in theory of mind had increased grey matter density after eight weeks of mindfulness training. It is generally assumed that increases in grey matter (neurons) result from repeated activation of a brain region, through a process of experience-dependent neuroplasticity. This study suggests that just eight weeks of training may induce neural rewiring in brain structures important for social cognition.

Taken together, these studies indicate that meditation impacts brain areas that are critical for theory of mind. However, when interpreting such results, it is important to remember that all of these brain regions are also involved in other mental processes. For example, the TPJ has been implicated in various forms of attention, as well as aforementioned self-related processes. Of course, one can argue that these other functions are important for developing theory of mind. Still, conclusions about the specific cognitive implications of these brain changes must remain tentative until more standard behavioral and cognitive testing is applied. In future studies, it would be fascinating to examine whether people who practice meditations that involve perspective-taking show changes in basic theory of mind tests, as well as related neural alterations.

Based on all we know about how the brain changes with repeated practice of any skill, it is reasonable to assume that theory of mind can be improved through intentional exercises. In some ways however, we don’t need brain scans to show this; you can engage in these kinds of contemplative practices and see if there are effects in your own life. Can you more easily imagine how others might be feeling? Are you moved toward caring and compassion? These will be the true indicators of meaningful change.